by Karl W. Reid, Ed.D.

As a young man raised in the Christian tradition, in our home and in Sunday School, “The Golden Rule” was drilled into our fiber: “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.” Jesus taught principle to his followers in the Sermon on the Mount.

So in everything, do to others what you would have them do to you, for this sums up the Law and the Prophets (Matthew 7:12, NIV).

My father was good at seizing moments to teach me these principles when he knew I was most likely to listen and learn, for instance after he “applied justice” to correct me when I was disrespectful to my mother or younger brother.

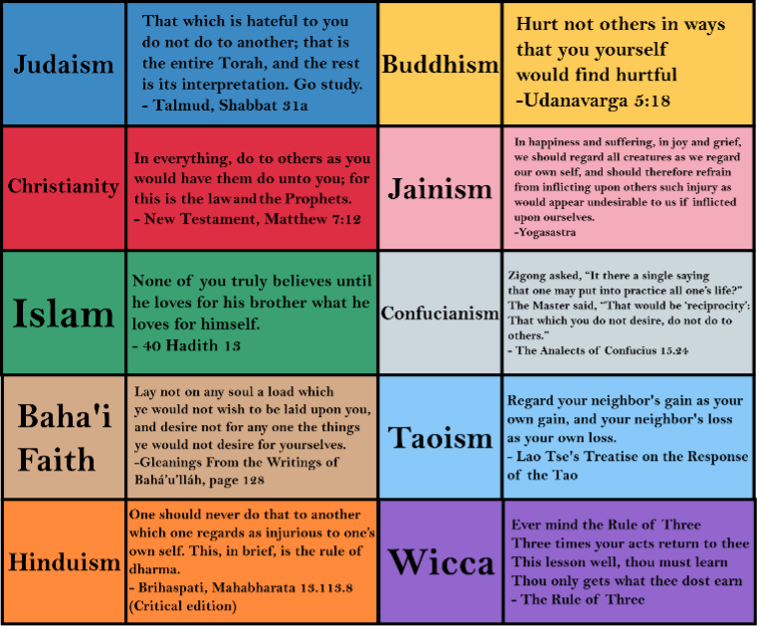

I later learned that many faith traditions teach variants of this “ethic of reciprocity”. The tenet could be positive or negative, for example to treat others as one would like to be treated as illustrated above, and in the prohibitive form, to not treat others as you would not like to be treated. Indeed, the United Nations posts a multi-faith poster showing the Golden Rule as articulated across religions:

The Golden Rule has guided an innumerable number of people (me included) dating back thousands of years. No doubt it has been used to resolve millions of conflicts that range from sibling rivalries to geopolitical wars.

My one problem with the Golden Rule, however, is that it centers the standard of treatment of others on…me, or you. The principle as stated localizes the measuring stick of “rightness” on the protagonist rather than asking how the individual prefers to be treated. What if the other person wants to be treated differently? What if your background and lived experiences are culturally, socially, or psychologically diverse such that the way you’d prefer to be treated would be upsetting or even offensive to another?

I never thought about this until I discovered The Platinum Rule.

The Platinum Rule

In their book, Say the Right Thing: How to Talk About Identity, Diversity, and Justice, Kenji Yoshino and David Glasgow coined the phrase to remind us to locate our actions within the perspective of another, to walk a mile in their shoes. The Platinum Rule “reminds you to take the other person’s preference seriously, whether by asking directly or by carefully reflecting on their needs” (p. 132). By applying this rule, allies avoid the inadvertent savior complex—a reflexive tendency among caring people to want to fix others, to help those who we believe need saving. The problem is that doing so without pausing first to consider whether the subject wants the kind of help or support we’re generously offering could miss the mark at best, or be off-putting at worse.

The Platinum Rule enhances the Golden Rule by urging you to help others as they would wish to be helped” (p. 132).

In other words, we must balance “doing good” with “doing no harm” as Yoshino and Glasgow write. An effective ally does both, with empathy and understanding.

The Golden Rule is a simple but powerful framework that goes back centuries. To be true allies, however, to walk in solidarity with the most marginalized and underserved among us, we position ourselves to listen in order to understand. Platinum is more precious than gold.

Warm regards,

Karl W. Reid, Ed.D.

Chief Inclusion Officer

Northeastern University